Read about Private Detective Claes Ekman - "when lawyers and police won't suffice" - in the academic journal / business magazine Civilekonomen.

Walhallen is a licensed private detective / private investigator group with associates / offices in nine countries (USA - Brazil - France - Germany - Sweden - Ukraine - Russia - China - Kenya) and ten cities (New York - Dallas - São Paolo - Paris - Berlin - Stockholm - Kiev - Moscow - Beijing - Nairobi). We specialize as private fraud / finance / business / matrimonial / commerce / industry detective-s / investigator-s.

Private Detective / Private Investigator Internet / Cyber Security in USA, Canada, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Europe (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Germany, Russia, Ukraine, France, Holland, England, Italy, Spain, et seq).

www.privatdetektiv-walhallen.com www.private-detective-walhallen.com www.walhallen.net www.walhallen.com www.wiiic.org www.bureau-ekman.com www.europadetektiv.com

Global Emergency Detective Telephone-s:

+46 730 983 700 (Europe-Asia-Middle East)

+1 205 2583 700 (North America/USA-Canada-Mexico - South America/Brazil-Argentine, et seq.)

+380 737 583 700 (Russia-Ukraine)

+212 600 983 700 (Morocco-Egypt-Kenya-Nigeria-South Africa - General Africa)

"I prefer organic creatures - more than ever - but if I occasionally miss one mechanical machine that I handle extensively as commanding pilot on private detective / private investigator missions in the United States and South America, it is this beauty." - Claes Ekman

PS. "This depicted 'old banger' might not impress anyone, albeit, I have recently been exceeding Mach 2.2 at 66,000 feet in another machine; an experience I'll share with you in due course."

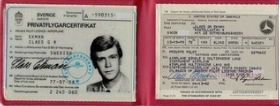

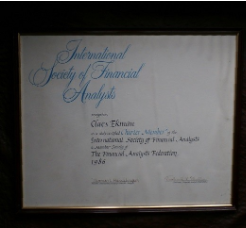

Private Detective Claes Ekman's International Society of Financial Analysts / U.S. Financial Analysts Federation Charter.

Private Detective Claes Ekman in TV documentary investigating terrorist recruitment in France, Germany and Holland.

Dear Citizen! 1st January MMXXV

After thirty years of international business / industry experience, we have chosen to concentrate and develop our private / finance detective firm, assisting companies, individuals and organisations - with an emphasis on commerce and finance - in Scandinavia and northeast Europe, also into the Americas, southwest Europe, Africa and Asia.

Winston Churchill quipped that "America will do the right thing - once it has exhausted all other opportunities"; and it is wildly dangerous to assume that Russia's future will simply be an extrapolition of its present, when even Russians say it is impossible to predict anything in their country - even the past; and the eurozone is confronted with a crisis of not just labour costs and prices - but of culture and work ethics - despite some of its members having pockets as deep as the Mariana Trench.

In extremis, amid global financial and trade conflicts, a self-sufficient America might see things occur that have not occurred before, although they have occurred in Europe, albeit [America] might confound the unusual with the abstruse.

Surely politicians recognize that entrepreneurs accept levels of risk that no rational person would contemplate, although, most people want one thing more than even love - i e, peace of mind. However, you can have both, because it is what you see, meet and come to experience everyday that makes you affectionate: a person [including yourself], an object, or why not a practice - and, "abeunt studia in mores". Alongside amour propre this is probably life's greatest gift.

Decline is not a condition but a choice, and instead of letting out a cri du coeur and eating humble pie, we would like to see finance less proud and industry more secure. A great many people are seduced en masse by politicians, and the pervading sense, increasingly widespread nowadays, is that companies are inherently immoral, even amoral, unless they demonstrate that they are the opposite - in effect, guilty until proven innocent."Der Zweifel ist's, der Gutes böse macht."

I am externally involved in only one other earthly enterprise - a strategic metals and advanced precision metal components group - and it is said that a man who has two women or horses loses his soul, and a man who has two houses loses his head. Albeit, I faithfully believe focusing on a real industrial entity broadens my horizon at times; however, despite requests for additional directorships, I will abstain from any further managerial excursions.

The inadmissible truth is that the eclipsing of life's other complications - but a passionate practice - is part of an earthly reward. It is a cognitive and emotional relief to immerse oneself in something all-consuming while other difficulties float by. The complexities of intellectual puzzles are nothing to those of emotional ones. Passionate work is a wonderful refuge, and the enjoyable pain passes but the beauty remains. L'homme c'est rien; L'oeuvre c'est tout - "The man is nothing; The work is everything".

Keeping your eyes on the ball-s is of utmost importance - particularly in intelligence work on the quiet one; flagds goti - and no man or no woman is worth more than any other, unless he or she achieves or performs more. No human is worth more than their deeds, maybe with the exception of an individual exercising and exploiting fata morgana. Many people actually believe what they say they believe!

The first commercial imperative must be to restore security; without security, running a business successfully, is like having "turtle soup without the turtle". You can use words, call something something - something it is not. One can deny what is and explain what is not - Ex nihilo nihil fit. To begin at the gentle end is to begin with the instrumentality of truth itself.

Occasionally, we find ourselves in the remarkable position that we do not know what we actually know. Things will not really be true until we say they are true. Intelligence / Investigator organizations must be built around a deference to the enormous difficulties which the search for truth often involves. This is by no means easy to achieve, but we see little merit in anything easy.

Sometimes when you are looking hard enough at something, when you are ready for anything that might shoot down your hypothesis, and nothing comes ... lack of disproof begins to feel like proof. What all this leaves us with, as one private detective / private investigator puts it, is "tonnes of conjecture and very little evidence". We need to verify what is and separate what is from what might be. Conjecture gives way to fact.

The famous philosopher Immanuel Kant once said: "All our knowledge begins with the senses." Kant with this statement proposed that all knowledge commences from the senses but "proceeds thence to understanding, and ends with reason, beyond which nothing higher can be discovered". Culture overall - whether personal, professional or national - is about matters of the mind; behaviour and actions are the observable outcomes of these preferences and the adherent knowledge.

The rhetorical criteria by which knowledge is tested and accepted and is thus transmitted successfully are themselves social conventions that are subject to cultural evolution. To say that propositions are accepted when they are supported by evidence is not much help, since it has to be specified what "supported" really means and which kinds of evidence are admissible.

A society in which "evidence" is defined as support in the writing-s of earlier sages would be very different from one that relied on experiments, but even the latter has to determine what experimental design is regarded as permissible and what outcome is accepted as decisive. Unlike what happens in biological evolution, cultural selection is not natural but is mostly conscious. The questions are what happens during the acquisition process and how are such choices made.

Persuasion and the diffusion of new ideas depend on many factors. One seemingly unassailable factor is that when knowledge is effective (that is, when techniques or predictions based on this knowledge work well), beliefs can change quickly. "The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance but the illusion of knowledge," as Stephen Hawking phrased it. I'd say human knowledge is personal and responsible, an unending adventure at the edge of uncertainty.

We may here distinguish between propositional and prescriptive knowledge, the former roughly corresponding to a genotype, the latter to an observable technique. There is no easy mapping between the two. Sometimes techniques are used with virtually no understanding of why and how they work. At other times, the necessary underlying knowledge may well be there, but the techniques fail to emerge. Moreover, there is no clear-cut casual between them; the best we can say is that they co-evolve.

All knowledge though is power, and the real test of "knowledge" is not whether it is true, but whether it strengthens us. Scientists usually assume that no theory is 100 per cent correct. (Ask any renowned physicist about the Quantum Theory versus Albert Einstein's Theory of Relativity, and you will get the answer that both theories are wholly true and correct, but they are not compatible with one another...) Consequently, truth is a poor test for knowledge. The real test is utility. A theory that enables us to do, for example, new things constitutes knowledge.

Our knowledge, and especially our scientific knowledge, progresses by unjustified (and unjustifiable) anticipations, by guesses, by tentative solutions to our problems; in a word by conjectures. Not only our knowledge, but also our aims and our standards grow through an unending process of trial and error, which must be subjected to critical tests.

A theory of experience may - and should - assign to our observations the equally modest and almost equally important role of tests which may help us in the discovery of our mistakes. Though, it should stress our fallibility, albeit, not resign itself to scepticism. It is vitally important to stress the fact that knowledge can grow and that science can progress - just because we can learn from our mistakes.

Anything that can not be reached by meagre knowledge and wisdom is beyond scientific control: it lays in the realm of genius, which rises above all rules. (Being aware that a tomato is in fact a fruit or berry is knowledge; not putting it in a fruit salad would be considered wisdom: a small reminder for those who can not differentiate between these two words.)

I share with many the penchant for delving into the genius of the past and asking how a similar knowledge spirit might guide the future. Knowledge is somewhat paradoxical. It is most productive when freely available. But the incentive to create it depends on the ability to restrict its use. The former consideration justifies dissemination. The latter justfies control. How, then, is this balance working?

Historically, knowledge has been [considered] dangerous. One anti-intellectual diatribe published in 1526 went so far as to pronounce knowledge "the very pestilence, that putteth all mankind to ruine and hath made us subjecte to so many kindes of sinne". Better, wrote the author, "to be Idiotes, and knowe nothinge" than to have one's head filled with pernicious ideas.

But although such thoroughgoing scepticism was an understandable reaction to the plethora of "knowledge" then on offer, it was a hard philosophy to stick to and nobody really did stick to it. It was more plausible to employ the weapons of Scepticism in a strictly limited way. Sceptical arguments were generally used to undermine outdated or overambitious claims to knowledge, not to attack all intellectual activity.

We suffer to such an extent from the illusion of the primacy of knowledge that we are immediately ready to make the philosphical knowledge of knowledge an idea idea. Wanting to express the obvious, we might define reflection or positional consciousness of knowledge as: "To know is to know that one knows." This would then transcend itself, and like the positional consciousness of the world it would be exhausted in aiming at its object. And that object would be consciousness itself.

There may be explanatory knowledge that is correct but scarcely satisfying. A private detective / private investigator may offer a certain hypothesis that might explain a crime, being told that the hypothesis is possible but not interesting, because reality has not the least obligation to be interesting. Reality can forgo an obligation, but hypotheses can not. Really? Me ne frego! Epistemology – the science investigating the nature and validity of knowledge – is no mean task.

Often there are indubitable evidence. We sense it. We reason it. Maybe the pleasure does not lie in discovering truth, but in searching for it. "And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free," as the saying in the Bible goes, and later adopted as mantra by the world's premier [public] intelligence organisation. The premier [private] one per eccellenza is ... another one.

Being able to develop Walhallen Finance / Business / Private Detectives into a truly integrated, global and robustly competent group is a privilege, and this mainly due to having the opportunity of gathering the most talented private investigators / private detectives available: from Russia-Ukraine-Finland-Germany-Sweden-Norway-Switzerland-France-China-Japan-USA-Kenya-Brazil, et seq.

Our private detectives, from armed forces - intelligence services - law enforcement - business - academia, will convincingly add value to customers and clients with positive terra firma ambitions for years ahead - and, not only in their own countries, albeit worldwide, which is our factual modus operandi: A Global Private Finance and Business Detective Group, specialising in industrial undercover work and counterindustrial espionage, including advanced Technical Surveillance CounterMeasures (TSCM) and computer forensics.

Walhallen's Private Investigator Cyber Defence / Internet Security Team is operating 24/7, confronting these anciens combattants in a bellum justum.

The first private detective / private investigator alarm / surveillance system installed and mounted by Walhallen some 36 years ago, and still operational. "Quality is free."

Walhallen's counter-surveillance equipment consists of several state-of-the-art systems second to none.

Private Detective Claes Ekman in TV documentary investigating terrorist activities in Sweden, Germany, England and USA.

As noted in a Walhallen Intelligence / Private Investigator Estimate Report: "The hostile intelligence threat to corporate / company computer systems is magnified by the enormous growth in the number and power of computers, the vast amount of data contained in them, as well as dismal Internet security measures. Computers multiply hugely the information to which a single individual may obtain access, hence the vast risk." For businesses, as well as for private individuals, we design, customize and implement encryption communications and storage software; 100% unbreakable.

"Having had a series of successfully solved private detective cases - commercial as well as criminal - in Asia and America, the competition, that is local private detectives and ditto lawyers, some with regional coverage, have come to question my evidence and experience in court and in the air. If 'sotto voce' sniping is any measure of [personal] freedom and 'sauve qui peut', facts are sacred." - Claes Ekman

Absence of voices / Absence of words ... Lost paths, lost thoughts, lost ideas ... Who are we missing?

What is the cavity in your existence? What has happened, or rather, what has happened that has not happened before; and why? Meet with us in London or New York - or anywhere - explaining your situation, in an honest attempt to find the truth.

We specialize in Logic, Language, Truth - and the Law.

Walhallen's professional experience in security and investigations, and its global reach - geographically, the most extensive amongst private detective / private investigator firms - allows it to advise its clients in ways which are unique in the private detective industry.

"TAKE EVERYTHING ON EVIDENCE. THERE IS NO BETTER RULE." Charles Dickens, novelist.

Perhaps you'll find evidence, proof and the truth through serendipity in Walhallen's alpine dwellings,

or in our ditto headquarters further east.

Not a great many or much dodge Walhallen's Astro Surveillance. Not this fella, nor these.

As noted in a Walhallen Intelligence / Private Detective Estimate Report: "The hostile intelligence threat to corporate / company computer systems is magnified by the enormous growth in the number and power of computers, the vast amount of data contained in them, as well as dismal Internet security measures. Computers multiply hugely the information to which a single individual may obtain access, hence the vast risk." For businesses, as well as for private individuals, we design, customize and implement encryption communications and storage software; 100% unbreakable.

Governments and private firms cannot afford to ignore cyber-attacks. Nor, indeed, can defense contractors. The size of the military and civil cyber-security market is an obvious why - it grew from $3.5bn in 2004 to $380bn in 2024. The market will expand by an annual 12-15% in the next three years, or twice as fast as global defense-equipment budgets.

Spurred on by Russian Internet attacks against the West, defense departments are considering spending far more on cyber-defenses. In America Congress is emphasizing the importance of cyber-security; Britain's government reportedly plans to shift some of the Ministry of Defense's budget towards repelling cyber-threats. Private-sector companies routinely put cyber-security among their top worries.

Today's rising demand for cyber-security services include the active identification of threats to providing executives with strategies about how to manage the fallout from attacks. Now that both governments and companies are suffering similar sorts of cyber-attacks, any actors that can leverage their historical expertise in military intelligence will excel.

Rise of the incognito Internet does not imply that the maxim of "nothing to hide, nothing to fear" should apply to Internet security... The peculiar psychology of code-breaking often involves one genius trying to work out what another genius has done, at times resulting in the most appalling carnage. To break a code - or the most abstruse cryptogram, even for an experienced private detective / private investigator - is to extend a hand to grasp the sky and hope to catch a bird.

Instead of unconditionally granting intelligence services more power, we need to worry about the coming convergence of the data-gathering demands of the state - nation state - and the business imperatives of Internet companies. This advice, however, compels us as a private detective / private investigator organisation to nothing that we should not otherwise have done.

To reveal the extent of the "suspicion-less" surveillance state is of vital importance. "Whoso would be a man must be nonconformist," as Ralph Waldo Emerson so eloquently put it. "Who are they? And whom do they think they are spying on?" The technology to spy on people has run way beyond the law. Any two individuals - whether in government or private enterprise - are perpetually striving to dominate, master, and possess one another; just as they strive to dominate the rest of their environment. However, if you cannot be monitored - not being under any sort of droit de regard - no one can control you.

Meaningful oversight has become impossible. Until we become conscious of this, we will never rebel. Even I - working with Internet security on a daily basis - sometimes feel like in kindergarten: limpingly espial; vigilant, primordial and tautly syllogizing the convoluted, esoteric ruse without derision or prerogative. If the intention is to collect everything from everybody, everywhere and to store it indefinitely, we have reached a turning point.

We can not find a place in our consciousness for such horror - ergo, someone is reading my private communication; see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil - or do we not have the imagination, together with the courage, to face it? Is it possible to live in a twilight between knowing and not knowing? We sense, or suspect (or perhaps the Nordic/Germanic ahnen which is more ambiguous but also stronger than "suspect"), [that] we are being overheard/listened to. But you cannot "sense" in a void; "sensing" is an inner realization of knowledge. Basically, if you "sense", then you know.

Any fool can criticize, condemn and complain, and most fools do, albeit, being quite au fait, should it be de rigueur with communications leaks, or should we dig in and wait for General Winter and a via media? An honourable approach and intelligence method must appeal to reason, abstraction and logic, framed by binary oppositions: conflict and harmony; morality and power. The fly in the ointment is, naturally, that we have the politicians we deserve. "Whose servants art thou?" Omne homo mendax - infra dignitatem - in sempiternum. As one politician, Dick Tuck, reasoned after a lost California State Senate race: "The people has spoken. The bastards."

In an ungoverned state, i e weak state - and civil libertarians may sniff a large rodent here - the individual is neither protected nor free, and "the strong may gnaw on the bones of the weak". The stronger the state, the freer is the individual. Democracy is the dictatorship - in a sense - of the law. However, "democracy is a device that ensures we shall be governed no better than we deserve," as George Bernard Shaw phrased it

I know there are many today who are afraid of order, albeit, order is nothing more than rules [being followed]. Omnipresent consensus may appear a beautiful thing, but good policy is better; and political ideology [as expressed with heart] is usually just an excuse for behaviour, rather than a reason for it.

If we could learn from history - some say - what lessons it might teach us! But passion and party blind our eyes, and the light which experience gives is a lantern on the stern, which shines only on the waves behind us. Can we demonstrate, perhaps, that the future will conform to the past, or at least offer some evidence that it will probably do so? No, but we can conclude that the past is a valuable guide to the future. Why can one expect certain events to be followed by certain other events, but reply to this only by stating that they have generally been found to do so.

Can some evidence be provided for the principle that the future will resemble the past, or can we just offer but evidence that it had done so in the past? Expectations and predictions are a matter of habit, and extrapolating from what has been observed is something that we are sensibly prone to do. However, in general, even reasonable and dialectic people are incapable of anticipating with gusto and presto a complex future.

The fact is that it is more a matter of instinct than of logic that we use the past as a guide to the future. It is even fortunate for us that we are naturally inclined to extrapolate from experience - rather than using abstract reasoning - because our lives depend on our ability to do so; though, as the saying goes, "The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there." In the context of forecasting and predictability, we might even be compelled to quote Blaise Pascal: "It is not certain that we shall see tomorrow; but it is certainly possible that we shall not."

Practical people - the many; hoi pollo - focus on the next moment and leave the centuries to dreamers, consciously incapable of anticipating the future. "Prediction is difficult, especially about the future," as the famous Danish nuclear physicist Niels Bohr formulated it. Most people would rather die than think and plan ahead. In fact they do. The idea of the future being different from the present is so repugnant to our conventional modes of thought and behaviour that we, most of us, offer a great resistance to acting on it in practice.

Europe's leading politician until 2020 (Jean-Claude Juncker) recently stated, "we all know what to do; we just do not know how to get elected after we have done it". (Another day, another stupid remark: people who "talk of sports and makes of cars, and daren't look up and see the stars".) Taking a tour d'horizon with this politician, you might as well let une couveuse shoulder la course en tête. Politics for these intermittents du spectacle means neither policy nor persuasion, but only taking stands; and their primum mobile is exactly what we sapere aude - "dare to know": getting elected. Humans must think for themselves.

Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel states personally: "Wir schaffen das", on immigration, and lately envisions "a true (this void denomination) European army". Slow progress towards common defence procurement, let alone a shared doctrine, renders loose talk about a European army ridiculous;"ein absoluter Schwindel", to paraphraze an earlier compatriot of the Chancellor.

There are times - they mark the danger point for a political system - when politicians can no longer communicate, when they stop understanding the language of the people they are supposed to be representing. The present constitutional means, and the literati tendency omnipresent, show us only the methods, not the [hidden] agenda. On immigration the proud German people responded Chancellor Merkel with "Wir sind das Volk". No doubt the Chancellor has been eating crow over whatever immigration deals she predicted would be smooth, including with Germany's more democratic neighbours Poland and Hungary.

Historical trends are the product of philosophy. To reverse today’s destructive political and cultural trends we must reverse men’s fundamental philosophy. If you don’t know what I am talking about, I couldn’t possibly explain it. If you do – I have you, already, without saying anything further.

Stefan Zweig wrote of his continent in the years leading up to the Second World War, “I felt that Europe, in its state of derangement, had passed its own death sentence – our sacred home of Europe, both the cradle and the Parthenon of Western civilization”. Zweig felt, though, the consolation that “What generations had done before us was never entirely lost”.

More than any other continent or culture in the world today, Europe is now deeply weighed down with guilt for its past. In Europe there is an existential tiredness and a feeling that perhaps for Europe the story has run out and a new story must be allowed to begin.

There is a desire by all-mighty political bureaucrats to demonstrate that in the twenty-first century, Europe has a self-supporting structure of rights, laws and institutions which could exist even without the sources – Greek philosophy; Roman law; Christianity - that had arguably given them life. No doubt a harsh climate (rough weather makes good sailors) and some excellent genetic strains paved the way for Europe's success.

Remember - and this is significant - that of the world’s 100 most valuable tech companies by stock market value in 2020, there remains only one (1) from Europe, Germany’s SAP; a company name most Europeans can’t place in the right context or even identify. And the Industrial Revolution commenced here…

Instead of remaining a home for the European peoples we have decided to become a “utopia” only in the original Greek sense of the word: to become “no place”. The Eastern European peoples and nations have shown some vision, objecting to the bullying from Brussels, and, saying “something has got to give” is not true. Often things just rub along badly for a very long time.

While childless Chancellor Merkel takes selfies with unauthorized immigrant youths screaming "Germany! Germany! Merkel! Merkel! – the majority (+60%) of whom did not even came from war-torn Syria - the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, told the people of Hungary that the new enemies of freedom were different from the imperial and Soviet systems of the past, that today they did not get bombarded or imprisoned, but merely threatened and blackmailed.

PM Orbán - as a glowing beacon among Europe’s politicians alongside Giorgia Meloni - stated, “At last, the peoples of Europe, who have been slumbering in abundance and prosperity, have understood that the principles of life that Europe has been built upon are in mortal danger. Europe is the community of free and independent nations; equality of men and women; fair competition and solidarity; pride and humility; justice and mercy." As a private detective working to a certain extent with immigrant criminality throughout Europe, I could not more agree than with this eminent politician.

Most Europeans have become unable to argue for themselves, therefore, turning himself directly to Brussels, PM Orbán further exclaimed: “It is the right of the European citizens to know what you are cooking up. There is a bubble here in Brussels, the virtual world of the privileged European elite, which has become detached from reality.” PM Orbán's truth reasoning is what political bureaucrats and academics call populism. Vox populi vox dei - "The voice of the people is the voice of God".

Dr Ezra Zubrov - the famous American anthropologist - computed that a difference of only 1 percent in mortality rates between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens who overlapped geographically, could have led to the extinction of the Neanderthals within thirty generations, well under a millennium. This reasoning (simple economics/mathematics; accumulated interest) applies roughly to nativity rates as well; alas, contemplate the potential contemporary outcome in the Occident after a migration deluge ... however, nothing is a worse guide to the future than common sense.

Like individuals, groups can become stuck in their ways, with fatal results. Forewarned, the proverb has it, is forearmed, and to let these decision-makers escape their cultural silos, people should question everything. With their mania for control, ghoulish politicians and bureaucrats cannot cope with a new world powered by innovation and creativity; and they do not fail the "marsch-mallow test", seeking instant gratification instead of waiting for greater rewards.

The entrepreneurial energy in evidence throughout the [Western] world is largely confined to the private sector - as it has always been - and they (entrepreneurs) should not have to sit in this bureaucratic mess and be disrespected. We lack leaders; successful leaders creating the right conditions so that others can achieve ambitious goals.

In honest truth - being neither a feminist, nor a chauvinist - the qualities men bring to the mix are what transformed the Western world from a backwater in the 16th century to where we are today [and changed the world]. The countries that have harnessed those male qualities of enterprise, discipline, energy, focus and a fierce desire to win have powered themselves to success.

"The civil Western man is born, lives, and die in slavery. At his birth he is sewn into swaddling clothes; at his death he is nailed into a coffin. As long as he retains a human form, he is chained up by our institutions," as Jean-Jacques Rosseau had it described.

Males have been brought up to sublimate feelings into competitive behaviour, and have been responsible for the vast bulk of the West's economic advance. The greatest obstacle for a continuation is the oppressive hand of the state, and the West's "rocket-ship trajectory" might be over unless this hand is removed (we would say that, wouldn't we?). It appears to me more appropriate to follow up the real truth of the matter than the imagination of it.

Business is one of the great creative forces - if not the greatest - propelling humanity forwards. Business is driven by competition - the drive to make something more beautiful, more efficient and more appealing than the other guy's product, and competition produces not just economic progress but also drama. Competition drives companies to innovate, and newness is the stuff of stories.

A business that is one of the richest sources of stories is crime, and we have seen Crime, Inc. turning into some of the most successful multinationals of recent years, as well as some of the most murderous; albeit, it also propels creativity. (Personally, I find it challenging hanging out with/talking to grave criminals [of stature...] - whether in custody, or at large - but that feeling is understandably and seldomly reciprocated.)

Politics - and common sense leadership in general - is all about taking people from a place they know to a place they do not know, to somewhere they have never been. And government - in essence not completely differently organised compared to a traditional protection racket - is simply the name we give to things we choose to do together.

The protection business is in fact the core around which most - if not all - nations have evolved. The one actor that monopolizes violence and organizes the protection on a certain territory, is also the one defining the rules its inhabitants must adhere to. Behind rules - the law - there is violence, brute force. We may distrust this authority and the violence it can always call on, but "commanding or obeying, it is all the same". The fee we pay is called tax.

We might argue - and you'd be surprised this reasoning coming from [one of] America's and Europe's most seasoned private detectives / private investigators - that without the growth and development of organized crime in America, that country might have done a lot less growing and developing itself.

According to this theory, nothing much happened in the middle decades of the last century without crooks facilitating or profiting from it, on hand to grease the economic wheels. Many renowned economists today actually believe that [moderate] corruption is, counter-intuitively, a lubricant for growth.

In many societies you do not buy loyalty and protection, you only rent it, and might makes right. It is like the way of rivers: those downstream bear the cost-s, those instrumenta vocale. We have two options: start running, or the other thing. It is a kind of interpretation, shared by many, who continue to view these hybrid bureaucrats/politicians as self-interested pragmatists who can be counted on to take the path of least resistance. Noblesse oblige et haute trahison en plain air.

We harbour a scathing scepticism of bureaucracies - especially the European Commission bureaucrazy - because they pursue their own agenda, gravitate towards the middle ground and drown decision-makers in paperwork. Successful government means escaping their influence. Asking bureaucrats if what they are doing is relevant, you might as well ask a barber if you need a haircut.

Those that give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserves neither liberty nor safety. The future will, unfortunately, most likely take a further distinctly dirigiste turn. Nevertheless, in the words of Yogi Berra, "you can observe a lot by watching".

"Trade follows the flag," declared Cecil Rhodes, and as globalization forces many companies to move strategic assets abroad, even to another continent - terra nullius / no man's land - there is a need to be en garde, if not actually aux armes. However, the Mafia - the Mob - the Cosa Nostra - the Camorra - the 'Ndrangheta - the Yakuza, and other criminal movements or structures are cunning, but no more.

(The properties of an organised movement, criminal or honourable, are spontaneity, impulsiveness, dynamic expansiveness - and a short life. The properties of a similar structure are inertia, resilience, and an amazing, almost instinctive, ability to survive.

The principle of the vis inertiae, for example, seems to be identical in physics and metaphysics/human design. It is not more true in the former, that a large body is with more difficulty set in motion than a smaller one, and that its subsequent momentum is commensurate with this difficulty, than it is, in the latter, that intellects of the vaster capacity, while more forcible, more constant, and more eventful in their movements than those of inferior grade, are yet the less readily moved, and more embarrassed and full of hesitation in the first few steps of their progress.)

Formidable as they might be, Mafia button-men do not have the intelligence training of a professional private detective/private investigator, and [they] are tabby cats next to panthers in this particular jungle. As private detective-s / private investigator-s we combat these daggers with inflexible determination, however, given the Underworld's predilection for deception, unique situations present us with some strange bedfellows.

In contacts with these and other monstra horrendum - before contacting private detectives / private investigators - I would paraphrase Theodore Roosevelt: "Speak softly, but carry a big stick." Often, when you want adult behaviour, treat people like babies; while we believe humans are rational, their behaviour is constantly the opposite.

There is only a casual relationship between human behaviour and logic. We simply cannot allow ourselves to assume that bad guys, or anyone else for that matter, will behave in a particular way under a particular circumstance. My experience has borne that out, over and over again. That [some] members of criminal organizations have minds like piranhas and the loyalty of rattlesnakes is, however, occasionally convenient.

To be beaten by one of your own is not as bad as be beaten by a foreign one, however; and roaring like a mouse, fighting like a flea, singing "Give me your arm, old toad; Help me down Cemetery Road", would make us appear useful idiots. A proper attitude can turn a burden to a blessing, a trial to a triumph. As Johann Wolfgang von Goethe expressed it: "Unglück ist auch gut."

The major misfortunes of life are not misfortunes at all but opportunities for self-improvement. Even Seneca - in his days - said that adversity was sent to test us, and that it was therefore a blessing in disguise because it enables us to develop our powers of endurance and other virtues.

Being part of a diaspora in dire straits, one can be comfortable imagining existing alongside an independent judiciary rather than in a smash'n grab society - Raubwirtschaft. However, possession is nine tenths of the law, and with foreign officials reasoning - "I am with my brother against a cousin, and with my cousin against a stranger" - many bona fide intentions will be jeopardized.

Growth and developing economies hide a thousand sins, and with the cruel clarity afforded by distance, you might realize you have interests rather than friends. For example, the recent murder of a middle-aged (41 year-old) British businessman - supposedly Aston Martin's representative in Beijing - and a close friend of one of China's fourteen most powerful politicians (Bo Xilai-now imprisoned for life), adds an international dimension to this country's most serious political upheaval in two decades, and exposes uncomfortable truths about how business and politics are conducted in the world's second-largest economy.

In this area of the world your enemy's enemy is probably your enemy too. A friendly feeling does not equalize a friendly intent; alas, often au contraire, a hostile intent blends very well with a friendly feeling.

Always use international, experienced private detective-s / private investigator-s in developing / transition economy countries when you need fast, accurate and reliable CCCI [Control-Command-Communications-Intelligence]. There are effective and efficient bureaus beyond Walhallen - that we can recommend - for a great many lesser undertakings. A key skill in investigative / intelligence management, as in litigation and negotiation, is the ability to quickly, ethically and effectively collect information about individuals who may pose a threat.

Too tough a bargaining for low private detective / private investigator retainer fees could cost you dearly, indeed - nota bene! - more precious things. Free armchair advice is always rich and plentiful. All that is excellent is as difficult to obtain as it is rare. Our international nature is central to our mission. Only investigators with experience around the world can hope to take on globe-spanning criminal networks.

The verb corrumpere means destroy in Latin, and having seen that [corruption], as plaintiffs' private detectives in commercial and criminal courts numerous times, we agreed to co-found The International Intelligence Institute of Commerce. The Principal Investigator of WIIIC welcomes any information of corruption, grand thefts, miscarriages of justice et cetera. "Shame and silence are cousins" - right? Sunlight is the best disinfectant; Lies cannot thrive in the light.

The Institute will be able to provide unbiased Independent Business Resolutions Schemes - lightening the burden of courts, prosecutors, lawyers, accountants, who often miss the "red flags" that private investigators detect - as well as carry out Forensic Audits and Impairment Tests; and this in addition to hosting an academic research and education group focusing on Intellectual Property and Patented Technology.

The Romans used to assess situations metaphorically, e g: Cum catapultae proscripta erunt, tum soli proscript catapultas habebunt - "When catapults are outlawed, only outlaws will have catapults". Their reasoning implies "rules replace common sense and reason". Maybe some laws are like some sausages; better not seeing them being made.

In a fair and just society, with archaic European and American legal practices - often hiding behind procedure - and an international institutional machinery that grinds along at a pace that would shame snails, preparedness is the key to success and victory. Western governments also often "piggy-back" on existing national investigations rather than undertake their own probes, creating "double jeopardy" by triggering separate prosecutions of the same case in different jurisdictions.

You learn in my business there aren't any rules, whether in corporate or business fraud cases, Internet/cyber-security or computer forensics cases, divorce or alimony cases; you are dealing with infinitely variable factors - the human heart and mind. My role is not to have a formula, and not to take one single thing for granted. It is my business, however, to know what other people do not know ... in particular regarding:

-business intelligence, corporate and international fraud, proof and accounting documentation, court preparations, taxes/VAT - calculations, general surveillance, missing person-s, debt collection and close personal protection.

-Internet/cyber-security, computer forensics and cryptography (the latter meaning "secret writing" in Greek).

-matrimonial affairs - divorce, child custody, infidelity and alimony.

There are truths which are not for all men, nor for all times; albeit, to a great mind nothing is little, and the humbler of our private detective / private investigator clients are usually the more interesting. Characterizing sought-after information as elementary does not, of course, imply that it is easy to get or even that it is a simple matter.

As a private detective since many years - in search of evidence and the truth - I prefer to begin at the beginning. Crime is common. Logic is rare. Therefore it is upon the logic rather than upon the crime that we should dwell.

- - - - - - - - - -

Is there an unquestionable Logic, an absolute Evidence, a perfect Truth, or an ultimate Justice? The estimation of a theory is not simply determined by its truth. It also depends upon the importance of its subject, and the extent of its applications; beyond which something must still be left to the arbitrariness of human opinion.*1; I,II)

In one respect, the science of logic differs from all others; the perfection of its method is chiefly valuable as an evidence of the speculative truth of its principles. To supersede the employment of common reason, or to subject it to the rigour of technical forms, would be the last desire of one who knows the value of that intellectual toil and warfare which imparts to the mind an athletic vigour, and teaches it to contend with difficulties and to rely upon itself in emergencies.

That which renders logic possible, is the existence in our minds of general notions, - our ability to conceive of a class, and to designate its individual members by a common name. The theory of logic is thus intimately connected with that of language. A successful attempt to express logical propositions by symbols, the laws of whose combinations should be founded upon the laws of the mental processes which they represent, would, so far, be a step towards a philosophical language.

Regarding logic as a branch of philosophy, and defining philosophy as the "science of a real existence", and "the research of causes", and assigning as its main business the investigation of the "why", while mathematics display only the "that", we contend, not simply, that the superiority rests with the study of logic.*2).

***

What is the difference between explaining "why" and describing "how"? Looking back, explaining "why" means to find casual connections that account for the occurrence of a particular series of events to the exclusion of all others. To describe "how" means to reconstruct this series of specific events that led from one point to another.

To comprehend phenomena in the purest rational way - i e, to deduce the why and how of things with mathematical certainty - is not only to see them "from the point of view of eternity," but in some sense to become part of the eternal. "Judge a man by his questions, rather than by his answers," as Voltaire so wisely advised us.

Any private detective / private investigator must elaborate on "Why?", which in its many variations is a question far more important in its asking than in the expectation of an answer. The first medieval punctus interrogativus (?) was defined as a mark that signaled a question which conventionally required an answer. In a ninth-century copy of a text by Cicero, a question is followed by a symbol that looks like a staircase, maybe implying that questioning elevates us.

What we want to know and what we can imagine are somehow, as well, the two sides of the same magical page. Curiosity in all its forms is the means of advancing from what we did not know to what we do not yet know. A vocabulary, a certain terminology, that we may face or experience, is nothing more than a means, a method.

Prior to experience, anything might be the cause of anything; it is experience - as well as abstractions of reason - which help us to understand life. Curiosity is born from the awareness of our own ignorance and prompt us to acquire, so far as possible, "a more exact and fuller knowledge of the object it represents."

Whether or not a question leads us up the garden path may depend not only on the words chosen to ask it but on the appearance and presentation of those words. We have long understood the importance of the physical aspect of the text, and not only of its contents, to transmit our meanings.

Every text depends on the features of its support, be it clay or stone, papyrus or computer screen. No text is ever exclusively virtual, independent of its material context: every text, even an electronic one, is defined by both its words and the space in which these words exist.

Every form of writing is, in a sense, a translation of the words thought or spoken into a visible, concrete representation. The question of the relation between the revealed word and human language is central. Language, we know, is our most effective tool for communicating but, at the same time, an impediment to our full understanding.

Nevertheless it is necessary to go through language in order to reach that which cannot be put into words. Language may materialize into something tangible, as "speech made visible". All writing is the art of materialized thought. "When a word is written," wrote Saint Augustine, "it makes a sign to the eye whereby that which is the domain of the ears enters the mind."

Writing belongs to a group of conjuring arts related to the visualizing and transmission of ideas, emotions, and intentions. Painting, singing, and reading are all part of this peculiar human activity born of the capacity to imagine the world in order to experience it. Language, even in Hell, grants us existence; and the intellect, the seat of language, is humankind's driving force, not the body, its vessel.

Readers belong to societies of the written word and, as every member of societies must, they try to learn the code by which their fellow citizens communicate. Not every society requires the visual encoding of its language: for many, sound is enough. The old Latin "scripta manent, verba volant", which is supposed to mean "what is written endures, but what is spoken vanishes", is obviously not true in all oral societies. That is also the meaning readers discover: only when read do the written words come to life.

Certainly the passage from spoken to written language was less an improvement in quality than a change in direction. Thanks to writing speakers are able to overcome the limitations imposed by time and space. Either as the inspiration that led to the invention of writing or as its consequence, the assumption that justifies the existence of writing as an instrument of thought is one of linguistic fatalism.

Just as everything in the universe can be given a name to identify it, and every name can be expressed in a sound, every sound has its representation. Nothing can be uttered that cannot be written down and read. Writing does not reproduce the spoken word: it renders it visible.

We use words to try to recount, describe, explain, judge, demand, beg, affirm, allude, deny - and yet in every case we must rely on our interlocutor's intelligence and generosity to construe from the sounds we make the sense and meaning we wish to convey. The abstract language of images helps us no farther, because something in our constitution makes us want to translate into words even these shadows, even that which we know for certain is untranslatable, immanent, unconscious. "A picture may say more than a thousand words, albeit,..."

A language can be incomprehensible because we have never learned it or because we have forgotten it: either case presupposes the possibility of an original communal understanding. Not to be able to communicate with one's fellow human beings has been compared to being buried alive.

The notion of a primeval single common language that was fragmented into a plurality of language bears a symbolic relationship to contemporary theories about the origins of our verbal capacities. Indeed, humans not only can learn an existing language but can take an active role in the shaping of new languages. These are words from Percy Bysshe Shelley in Prometheus unbound:

"He gave man speech, and speech created thought,

Which is the measure of the universe."

Language is "the beginningless and endless One", the imperishable of which the essential nature is the Word. Language is continuous and co-terminus with human existence or the existence of any sentient being. Things perceived and things thought, as well as the relationship among them, are determined by the words that language lends them. (Further on we will delve deeper into the real meaning-s of words.)

We name things and images - in words. Socrates argues (or at least, puts forward the suggestion) that "names rightly given are the likeness and images of the things which they name", but goes on to say that it is nobler and clearer to learn from the things themselves rather than from their images.

A name defines us from outside. Even if we choose a name to call ourselves, the identity purported by the name is exterior, something we wear for the convenience of others. Names, however, sometimes encapsulate an individual essence. "Caesar I was, and now I am Justinian," proclaims the emperor who codified the Roman system of law in the sixth century, and sort of redefines himself as he acts and implements a new system.

In an effort to translate the idea that things are metaphors of themselves, that in an effort to translate the experience of reality into language, we sometimes see things as the words that name them, and the feature of things as their incarnated script. The question "Who am I?" is, however, no more fully answered by a name than a book is revealed fully by its title.

***

The pursuits of the mathematician, or the technician, "have not only not trained him to that acute logical scent", to that delicate, almost instinctive, tact which, in the twilight of probability, the search and discrimination of its finer facts demand; they have gone to cloud his vision, to indurate his touch, to all but the blazing light, the iron chain of demonstration, and left him out of the narrow confines of his science, to a passive credulity in any premises, or to an absolute incredulity in all.

The reason of which is cultivated by the abstractly logical is the only valuable form available, not reason educed by mathematical study. The mathematics are the science of form and quantity; mathematical reasoning is merely logic applied to observation upon form and quantity. The great error lies in supposing that even the truths of what is called pure algebra, are abstract or general truths.

Mathematical axioms are not axioms of general truth. What is true of relation - of form and quantity - is often grossly false in regard to morals, for example. In this latter science it is very usually untrue that the aggregated parts are equal to the whole. In chemistry also the axiom fails. In the consideration of motive it fails; for two motives, each of a given value, have not, necessarily, a value when united, equal to the sum of their values apart.*3; I,II)

It is an important observation, which has more than once been made, that it is one thing to arrive at correct premises, and another thing to deduce logical conclusions, and that the business of life depends more upon the former than upon the latter. The study of the exact sciences may teach us the one, and it may give us some general preparation of knowledge and of practice for the attainment of the other, but it is to the union of thought with action, in the field of Practical Logic, the arena of Human Life, that we are to look for its fuller and more perfect accomplishment.

If we want to study the problems of truth and falsehood, of the agreement and disagreement of propositions with reality, of the nature of assertion, assumption and question, we shall with great advantage look at primitive forms of language in which these forms of thinking appear without a confusing background of highly complicated processes of thought.

When we look at such simple forms of language, the mental mist which seems to enshroud our ordinary use of language disappears. We see activities, reactions, which are clear-cut and transparent. On the other hand we recognize in these simple processes forms of language not separated by a break from our more complicated ones. We see that we can build up the complicated forms from the primitive ones by gradually adding new forms.

We investigate whether e g "Brick" means the same in the primitive language as it does in ours; and then this goes with our contention that the simpler language is not therefore an incomplete form of the more complicated one. We make it plain that words have the meanings we give them, and that it would be a confusion to think of an investigation into their real meaning. (We might refer to Humpty Dumpty for an ascending logical height: "When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less!")

If you have not distinguished between a language and a notation, you may hardly see any difference between following a language and following a notation. But in that case you may well be unclear about the difficulties in connection with the relation between language and logic. Much of all this can be answered by emphasizing that speaking and writing belong to intercourse with other people. The signs get their life there, and that is why a language is not just a mechanism.

What is the meaning of a word? Let us attack this question by asking, first, what is an explanation of the meaning of a word; what does the explanation of a word look like? The way this question helps us is analogous to the way the question "how do we measure a length?" helps us to understand "what is length?"

Asking first "What's an explanation of meaning?" has advantages. You in a sense bring the question "what is meaning?" down to earth. For, surely, to understand the meaning of "meaning" you ought also to understand the meaning of "explanation of meaning".

What one generally calls "explanations of the meaning of a word" can, very roughly, be divided into verbal and ostensive definitions. If the definition explains the meaning of a word, surely it can't be essential that you should have heard the word before. It is the ostensive definition's business to give it a meaning.

I point this out to remove, once and for all, the idea that the words of the ostensive definition predicate something of the defined; the confusion is grave between the sentence "this is criminal", attributing the [culpable] etiquette to some human behaviour or act, and the ostensive definition "this is called criminal".

However, the thought is not [always] the same as the sentence; for an English and a French sentence, which are utterly different, can express the same thought. A phrase or sentence has sense, if we give it sense. We know what a word, or a row of words, means in certain contexts, at specific times and/or geographical locations.*4)

We can here also note a consistent conceptual dilemma. The meaning of a word often depends not just on its dictionary definition and the grammatical context but the meaning of the rest of the sentence. We realize that "the pen is in the box" and "the box is in the pen" require different meanings/translations for "pen": any pen big enough to hold a box would have to be an animal enclosure, not a writing instrument.

Giving a reason for something one did or said means showing a way which leads to this action. At this point, however, another confusion sets in, that between reason and cause. One is led into this confusion by the ambiguous use of the word "why". This when the chain of reasons has come to an end and still the question "why" is asked, one is inclined to give a cause instead of a reason.

The difference between the grammars of "reason" and "cause" is quite similar to that between the grammars of "motive" and "cause". Of the cause - cause in this context naturally only a logical one, not physical, nor medical - one can say that one can not know it but can only conjecture it. For a private detective / private investigator this is of vital importance de jure!

The double use of the word "why", asking for the cause and asking for the motive, together with the idea that we can know, and not only conjecture, our motives, gives rise to the confusion that a motive is a cause of which we are immediately aware, a cause "seen from the inside", or a cause experienced. Giving a reason is like giving a calculation by which you have arrived at a certain result.*5; I,II,III,IV,V)

In themselvselves, causes can be divided or refined into three sub-groups: in fieri causes, i e, in becoming or in progress dittos; in esse causes, i e, in actual existence dittos; and, lastly, in posse causes, i e, in potential or in the state of being possible dittos. That causes can have deux origines - primary and secondary; and more - is another interesting observation. The sobering truth is that everything is determined by a cause "which is also determined by another, and this again by another, and so to infinity."

Most observers maintain that the main function of theoretical reasoning is to enhance individual cognition – a task it performs abysmally. (The word Theory comes from the Greek word Theōria or Theoría, meaning “looking at, gazing at, being aware of”.) Psychologists generally recognize that reason is biased and lazy, that it often fails to correct mistaken intuitions, and that it sometimes makes things worse.

When people disagree but have a common interest in finding the truth or the solution to a problem they start to exchange arguments with each other. The best idea tends to win; whoever had it from the beginning or came to it in the course of the discussion is likely to convince the others. (This is what professional politicians dismiss as populism.)

Reason is more efficient in evaluating good arguments than in producing them, and reason is first and foremost a social competence. However, reason can bring intellectual benefits as the case of science well illustrates, by and through interaction with others. Reason is not a superpower implausibly grafted onto an animal mind; it is, rather, a well-integrated component of the extraordinarily developed mind that characterizes the human animal.

Alas, Descartes justified his rejection of everything he had learned from others by expressing a general disdain for collective achievements. The best work, he maintained, is made by a single master. What one may learn from books, he considered, “is not as close to the truth, composed as it is of the opinions of many different people, as the simple reasoning that any man of good sense can produce about things in his purview”.

Why did Descartes decide to trust only his own mind? Did he believe himself to be endowed with unique reasoning capabilities? On the contrary, he maintained that “the power of judging correctly and of distinguishing the true from the false (which is properly what is called good sense or reason) is naturally equal in all men”. But if we humans are all endowed with this power of distinguishing truth from falsity, how is it that we disagree so much on what is true?

Martin Luther stated that “Reason is by nature a harmful whore. But she shall not harm me, if only I resist her. See to it that you hold reason in check and do not follow her beautiful cogitations. Throw dirt in her face and make her ugly.” In another context, the same Luther described reason, much more conventionally, as “the inventor and mentor of all the arts, medicines, laws, and of whatever wisdom, power, virtue, and glory men possess in this life” and as “the essential difference by which man is distinguished from the animals and other things”.

Perhaps Luther avoided a reason discussion for religious propaganda objectives, but still, if we were to put reason on trial, both the prosecution and the defense could make an extraordinary case. The defense would argue that humans err by not reasoning enough. The prosecution would argue that they err by reasoning too much. The defense and the prosecution could also produce compelling narratives to bolster their case.

The two words “reasoning” and “inference” are often treated as synonyms. We might state that reasoning is only one way of performing inferences, and not such a reliable way at that. We might pose a question: Is this process – attending to reasons – the only way to pursue the goal of extracting new information from information that we already possess? Of course not! After all, even animals form expectations about the future. Their life depends on these expectations being on the whole correct. Since the future cannot be perceived, it is through inference that animals must form expectations. It is quite implausible, however, that, in so doing, animals attend to reasons.

Some institutions put a premium on well-crafted arguments. Lawyers only get one final plea. Politicians must reduce their arguments to efficient sound bites. Scientists compete for the attention of their peers: only those who make the best arguments have a chance of being heard. To some extent, reasoning rises to these challenges. With training, professionals manage to impose relatively high criteria on their own arguments. In most cases this improvement transparently aims at conviction. Lawyers must persuade a judge or a jury. If there are other people, including the lawyers themselves, whom arguments fail to convince, so be it.

By contrast, scientists – and I might humbly add private detectives / private investigators – seem to be striving for the truth, not for the approval of a particular audience. We suggest that in fact their reasoning still looks for arguments intended to convince but that the target audience is large and is particularly demanding. If anyone finds a counterargument that convinces the scientific community, the scientist’s argument is shot down. She cannot afford to appeal to a judge’s inclinations or to play on a jury’s ignorance of the law.

Experts in a given scientific field are likely to share much of the information relevant to settle a disagreement. This makes actual argumentation much more efficient. This also improves the power of individual reasoning. Of all the scientific communities, mathematicians are those who are most likely to recognize the same facts and to be convinced by the same arguments - they share the same axioms, the same body of already established theorems, and the arguments they are aiming at are proofs.

From a formal point of view, a proof is a formal derivation where the conclusion necessarily follows from the premises. From a sociology of science point of view, a proof is an argument that is considered, in a scientific community, as conclusive once and for all. In logic and mathematics, the formal and the sociological notions of proof tend to be coextensive.

Reason is one module of inference among many. Inferential modules are specialized: they each have a narrow domain of competence and they use procedures adapted to their narrow domain. This contrasts with the old and still dominant view that all inference is done by means of the same logic (or the same probability calculus, or logic plus probabilities).

Reason draws inferences about reasons! This may look like a vague truism or a cheap play on words – a theatrical semantics exercise (at least in English and in Romance languages, where a single word of Latin origin refers both to the faculty of reason and to reasons as motives). Yet in the history of philosophy and of psychology, reason and reasons have been studied as two quite distinct topics.

An individual stands to benefit from having her justifications accepted by others and from producing arguments that influence others. She also stands to benefit from evaluating objectively the justifications and arguments presented by others and from accepting or rejecting them on the basis of such an evaluation. These benefits are achieved in social interaction, but they are individual benefits all the same.

As private detectives / private investigators - in language games, in philosophical investigations, and in reality - we often encounter what could best be conceived by the Greek word aitia, meaning both cause and guilt; a fact. And, as Mark Twain described the latter: "Facts are stubborn."*6; I,II,III)

Instead of "craving for legal generality" I could also have said "the contemptuous attitude towards the particular case". If, e g, someone tries to explain the concept of number and tells us that such and such a definition will not do or is clumsy because it only applies to, say, finite cardinals I should answer that the mere fact that he could have given such a limited definition, of for example a crime sequence, makes this definition extremely important to us. (Elegance is not what we are trying for as truth seekers.)

Philosophy, as we use the word, is a fight against the fascination which forms of expression exert upon us. Many questions can be raised. Socrates asked: "What is knowledge?" Saint Augustine asked: "What is time?" We ask: "How can we hang a thief who does not exist?" One answer to the latter can, by a private detective - private investigator, be put in this form: "We can not hang him when he does not exist, but we can look for him when he does not exist."*7)

Our investigative method is purely descriptive; the descriptions we give are not hints of explanations. Think of words as instruments characterized by their use [...] "It is no act of insight which makes us use the rule-s as we do," because there is an idea that "something must make us" do what we do. And this again joins on to the confusion between cause and reason. We need have no reason to follow the rules as we do. The chain of reasons has an end.

Many pundits will say, no doubt, please use the language of the law, [that] "to make out your case". This may be the practice in law, but it is not the usage of reason. My ultimate objective is only the truth. Reason feels its way, in its search for the true. Alas, as the philosopher David Hume formulated his experience briefly: "'tis not reason, which carries the prize, but eloquence." Maybe he was right.*The elaborate truth reasoning of Nicolas Malebranche - freely translated from French - is indeed recommended. 8;l,ll,lIl)

Many find it sagacious to echo the small talk of lawyers, who, for the most part, content themselves with echoing the rectangular precepts of the courts. I would here observe that very much of what is rejected as evidence by a court is the best evidence to the intellect. For the court, guided itself by the general principles of evidence - the recognized and booked principles - is averse from swerving at particular instances.*9)

Participants in the system or legal complex will state that "we're doing what we're supposed to be doing - we're weighing the evidence, we're thinking it through, in a collective, collaborative, bipartisan way;" - and that is old hat. People don't have differences because they have different information or intelligence. We are often all looking at the same things. I think the differences depend more on your past experience, the contemporaneity and die Zeitgeist; and the old rule that "one can only be judged by one's peers" has great bearing and validity.*10)

The consummate philosopher Benedictus Spinoza, whom we venture to quote, says [post-mortem] in the discussion that closes Part I of The Ethics, that "everyone judges of things according to the state of his brain". In the same treatise he interprets the proverb, "brains differ as completely as palates", to mean that "men judge of things according to their mental disposition". It must be that one - or this or that particular - single brain, being wider than the sky, can comfortably accommodate a good man's intellect and the whole world besides.

A theory based on the qualities of an object, will prevent it being unfolded according to its objectives; and he who arranges topics in reference to their causes, will cease to value them according to their results. Thus the jurisprudence of every nation will show that, when law becomes a science and a system, it ceases to be justice. The errors into which a blind devotion to principles of classification has led the law, will be seen by observing how often the legislature has been obliged to come forward to restore the equity its scheme had lost.

Do we have revolutionary, or evolutionary, true justice; or the "Absolute paradox" of excessive cleverness? All professions are a conspiracy against the laity, and one way that conspiracy manifests itself - especially amongst lawyers - is in the use of jargon, so that outsiders cannot follow what is going on.

Another tendency is to belittle the contribution that other professionals, more or less intelligent, make. In order to eradicate "inconvenient truths" we might fall back on a kind of nominal legalism, in which the law is less protecting the citizenry than being an instrument of power. Many human beings, learned as well as ignorant, smart as well as stupid, are led into some state of uncertainty and ambivalence. They are looking but not seeing, like fish living in the ocean without knowing of the ocean.*11; I,II,III)

In support of these and other charges, as a private detective / private investigator, both argument and copious authority are adduced. I shall not attempt a complete discussion of the topics which are suggested by these remarks. My object is not controversy, and the observations made are offered not in the spirit of antagonism, albeit in the hope of contributing to the formation of just views upon an important subject.

The expression of a truth cannot be negatived by a legitimate operation, but it may be limited. The equation y = z implies that the classes Y and Z are equivalent, member for member. Multiply it by a factor x, and we have

xy = xz,

which expresses that the individuals which are common to the classes X and Y are also common to X and Z, and vice versâ. This is a perfectly legitimate inference, but the fact which it declares is a less general one than was asserted in the original proposition.

Such is indeed the actual law of scientific progress. We must be content, either to abandon the hope of further conquest, or to employ such aids of symbolic language, as are proper to the stage of progress, at which we have arrived. Nor need we fear to commit ourselves to such a course. We have not yet arrived so near the boundaries of possible knowledge, as to suggest the apprehension, that scope will fail for the exercise of the inventive faculties.

Language, symbolic or not, however, is an instrument of logic, but not an indispensable instrument. Every proposition which language can express may be represented by elective symbols, and the laws of combination of those symbols are in all cases the same; but in one class of instances the symbols have reference to collections of objects, in the other, to the truths of constituent propositions.

Now the question of the use of symbols may be considered in two distinct points of view. First, it may be considered with reference to the progress of scientific discovery, and secondly, with reference to its bearing upon the discipline of the intellect. It may be observed that as it is one fruit of an accomplished labour, that it sets us at liberty to engage in more arduous toils, so it is a necessary result of an advanced state of science, that we are permitted, and even called upon, to proceed to higher problems, than those which we before contemplated.

The practical inference is obvious. If through the advancing power of scientific methods, we find that the pursuits on which we were once engaged, afford no longer a sufficiently ample field for intellectual effort, the remedy is, to proceed to higher inquiries, and, in new tracks, to seek the difficulties yet unsubdued.

The scarcely less momentous question of the influence of the use of symbols upon the discipline of the intellect, an important distinction ought to be made. It is of most material consequence, whether those symbols are used with a full understanding of their meaning, with a perfect comprehension of that which renders their use lawful, and an ability to expand the abbreviated forms of reasoning which they induce, into their full syllogistic development; or whether they are mere unsuggestive characters, the use of which is suffered to rest upon authority.

The order of attainment in the individual mind would bear some relation to the actual order of scientific discovery, and the more abstract methods of the higher analysis would be offered to such minds only, as were prepared to receive them.

It may not be inappropriate, before concluding these observations, to offer a few remarks upon the general question of the use of symbolic language in the jurisprudence / the private or public investigative science. Objections have lately been very strongly urged against this practice, on the ground, that by obviating the necessity of thought, and substituting a reference to general formulæ in the room of personal effort, it tends to weaken the reasoning faculties.

However, logic must like, for example, geometry rest upon axiomatic truths, and its theorems must be constructed upon the general doctrine of symbols, which constitutes the foundation of the recognized analysis. It is no escape from the conclusion to which it points to assert, that logic not only constructs a science, but also inquires into the origin and the nature of its own principles, - a distinction which is denied to, for example, mathematics. (It is wholly beyond the domain of the mathematicians to inquire into the origin and nature of their principles.)

With the advance of our knowledge of all true science, an ever-increasing harmony will be found to prevail among its separate branches, including the paramount value and importance of the study of morals. All sincere votaries of truth may meet and agree that it is the "characteristic of the liberal sciences, not that they conduct us to virtue, but that they prepare us for virtue". Die einfachen Wahrheiten des Lebens, however, is [as mentioned before, and worth repeating] that everything - including virtue - is determined by a cause "which is also determined by another, and this again by another, and so to infinity".

On moral matters, and concerning the abundance of empty unintelligible noises and jargon describing virtue, one must beware of the hordes of journalists, politicians, and other "we-know-it-all"-pundits, who cover their ignorance with a curious and unexplicable web of perplexed words. With a sense of responsibility for the welfare of all, we must stay close to common sense, avoid raising [an existing] political paradox into profound truth, albeit, instead realize that full truth will not come in a flash (if it will ever come).

Beware, "no impression arising from something true is such that an impression arising from something false could not also be just like it". In other words, an illusion could be just as convincing as the real thing (that, indeed, is the point of illusions), so you might not be able to tell the difference between them just by looking.